My grandmother used to say that! It is more than an affectionate memory: it is the gateway to a heritage of folk and linguistic wisdom that Graziano Delorda and Lelio Bonaccorso’s volume brings back to light, restoring Sicilian to its role as a living language, rooted in memory and open to the future.

Quite some time ago I was in France for study. I happened, one day, to meet an Italian-American tourist who, having heard me speak Italian, engaged in a dialogue with me. At one point he says to me, “I have been in Italy and I had some difficulties to make myself understood with my Italian, while I see that you understand me without problems” And I retort, “I understand you because I am Sicilian. In fact you don’t speak real Italian, but Sicilian.” Yes, the oldest members of the Siculo-American communities are, today, in some ways, the true custodians of the Sicilian language.

The Sicilian language

Yes, I said language and not dialect, because Sicilian has been recognized as an endangered regional language by UNESCO and classified as a language, that is, an autonomous idiom, by the International Organization for Standardization, which has given it the ISO 639-3 scn code. Sicilian, possesses, in fact, its own vocabulary, grammar and syntax. It does not derive from Italian, but directly from Vulgar Latin and has spread not only in Sicily but also in south-central Calabria and Salento in Apulia. Not everyone knows that Sicilian established itself as an Italian literary language as early as the first half of the 13th century, thanks to the ruler Frederick II of Swabia, nicknamed “Stupor Mundi” because of his vast knowledge and many interests. In fact, he fostered the birth of the Sicilian School with poets and men of letters who wrote in the Sicilian vernacular and who had a lasting and significant influence in the formation of Italian literature. Having been the first Italian literary language, Sicilian could establish itself as the official language of Italy. Unfortunately, it did not succeed against the Florentine language, which experienced a wider diffusion in the Italian territory, thanks to Dante Alighieri and his Divine Comedy.

Today, in Sicily, people speak a watered-down Sicilian. It has, in fact, Italianized. I, who left Sicily in 1965, when, returning there for summer vacation, I try to speak my Sicilian, not everyone understands me, because it is the Sicilian of the 1960s, which had been, still, little contaminated by the Italian language.

In order to find the true Sicilian language, it is necessary to refer to the writings of poets and novelists who used such language in times past. Noteworthy are, for example, the works in Sicilian by the Mexican writer and poet, Maria Costa.

Migrants custodians of the Sicilian language

Then, as I mentioned earlier, we can consider as repositories of the most authentic Sicilian language the thousands of Sicilian migrants, who moved to different countries around the world, between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Keeping alive the customs, traditions, idiom, of their places of origin, also for and among their future generations.

My grandfather, for example, who landed in Philadelphia in 1927, brought Sicilian with him as his linguistic “baggage.” He was a farm laborer and knew little Italian. At home, in America, they spoke Sicilian, and his family knew, of Italy, that language, which did not change at all, because they lacked the influence of Italian, since around them people spoke mostly English.

The promotion of the Sicilian language

Since Sicilian is a language at risk of extinction, initiatives to keep it alive are multiplying in Sicily. Important and commendable is the commitment of the Center for Sicilian Philological and Linguistic Studies in Palermo in promoting studies on the ancient and modern island idiom. So is the commitment of the Cademia Siciliana association, which aims to pursue various initiatives related to the Sicilian language, including the standardization of its orthography, its dissemination in the computer environment and scientific dissemination in the philological field. Also very important was the action of the Sicilian Region, which in 2011 passed a lawto encourage the promotion of Sicilian language heritage and literature in the schools of Sicily. Thanks to this law today many young Sicilians are rediscovering, in their school classes, the Sicilian language and thus a not insignificant part of their roots.

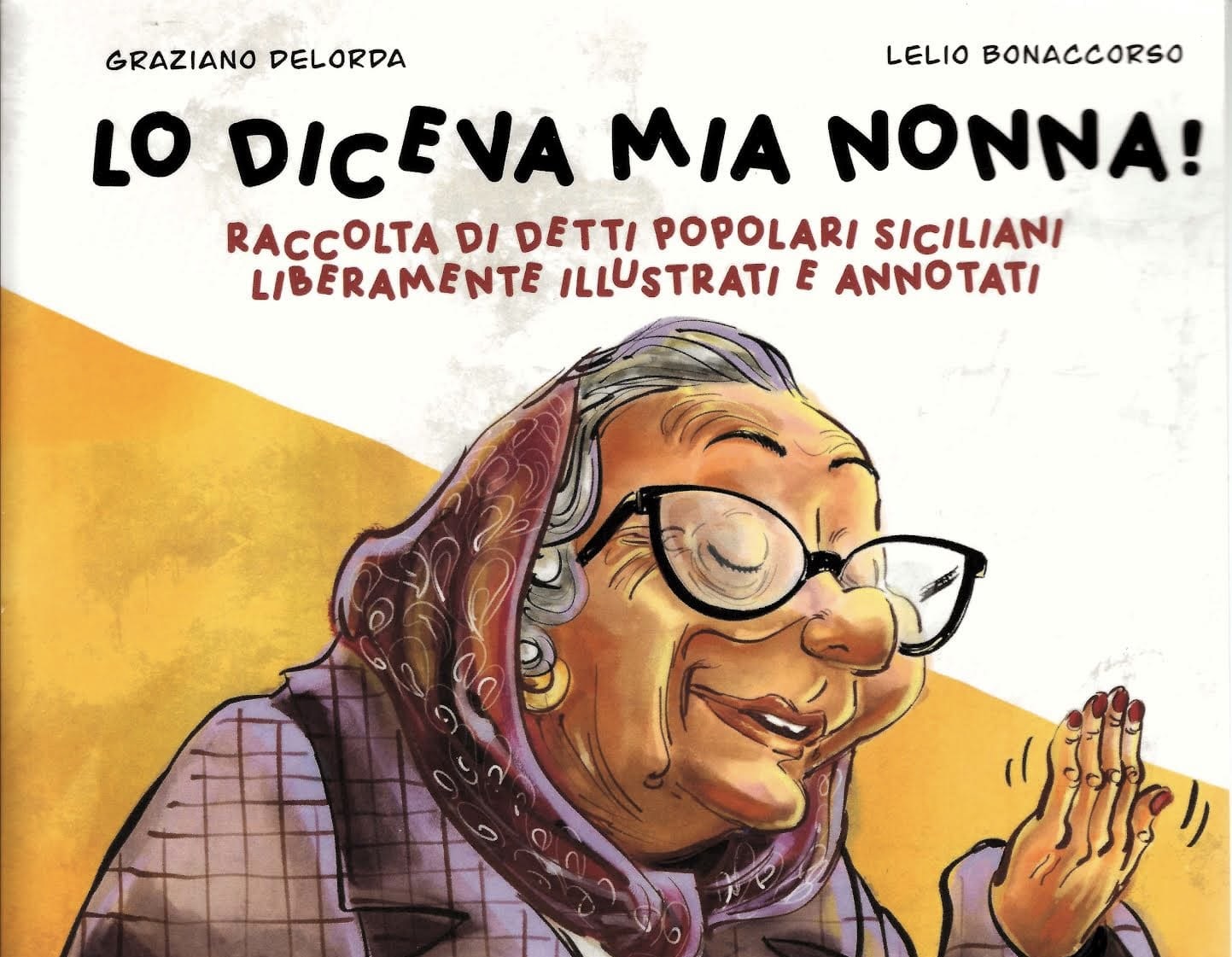

MY GRANDMOTHER USED TO SAY!

The booklet “Lo diceva mia nonna” with texts written by Graziano Delorda, a Sicilian writer, and illustrated by Lelio Bonaccorso, a cartoonist and cartoonist who is also Sicilian, in circulation since last June on online sales sites, fits magnificently within this program of revival of the Sicilian language, recovering and spreading those sayings, idioms, popular proverbs, bearers of an ancient, but still very effective wisdom. Sayings in use, even today, in many Sicilian families, mine included, to clarify, in a joke, sometimes even ironic, concepts of great importance and relevance of daily living. I knew only a good part of the sayings contained in the booklet; it was, therefore, enriching to me. In addition, I learned their origin and provenance, always an object of curiosity for me. My wife and I, thanks to “My grandmother said it!” have, today, at our disposal other expressions to emphasize or clarify certain concepts, certain thoughts, certain ideas, certain notions. In addition, this summer I involved, in the reading of the little volume, also my 17-year-old granddaughter, who lives in Florence. She has always loved the Sicilian language. In our house she uses, often, the Sicilian cadence in speaking, even inserting, in her speeches, Sicilian words. She became so fond of some of those idioms that she wanted to learn them by heart, employing them, right away, to reinforce her concepts and thoughts.

We now look forward to the second volume, which is in preparation, to expand our available Sicilian sayings.

The authors

Graziano Delorda is a Sicilian writer and novelist. He has to his credit such novels as “Peace” from 2010, “Little Olive” from 2016 and “Droid is the Night” from 2017. There is also a 2011 collection of short stories titled “The Black Serpent.”

Lelio Bonaccorso is a Sicilian cartoonist, illustrator and poet. He is the author of numerous graphic novels produced in collaboration with prominent writers and scriptwriters. Among these noteworthy are “Salvation,” “At Our House…chronicle from Riace,” “Peppino Impastato, a jester against the Mafia,” “Jan Karski, the man who discovered the Holocaust,” “Wind of Freedom,” “Sinai, the moonlit land,” “For the Love of Mona Lisa,” “Caravaggio and the Girl,” and “My Second Generation.” Some of his works have also been translated and published in Spain, France, Germany, Holland, Belgium, the USA, Canada, Latin America, and Poland. In the UK in 2024 he published “Spider-Man Magazine” for Disney/Marvel. He also has to his credit a book of poems “Flowers of Wind,” which was nominated for the Strega Poetry Prize in 2023.

The article “My grandmother said it!” – Sicilian sayings between memory and future comes from TheNewyorker.